Once upon a time, there was a girl who was a bowling champion.

Actually, she was pretty awesome at just about everything she did: she was a champion, in general. But it started at the bowling alley.

I remember the beginning. One Saturday morning when I was eight or so, my mother brought me to a tiny downtown bowling alley: Quilles Ste-Anne. The place was tiny, six lanes and five-pin only, and hard to find, built as it was in the basement of a building that sat in the middle of a parking lot behind a church.

I don’t remember who handed me my first bowling ball. I do remember being taught to hold it between my spread legs and lob it down the lane with both hands. Which was, to my eight-year-old self, unacceptable. Looking around I could clearly see that this was how babies bowled. I was not a baby. I demanded to be shown the right way to bowl, or I wasn’t going to bowl at all.

It seems clear to me now that this is the moment that I started to tell myself the story of myself. Item one: Linda Bayley is not a baby.

Over the years, the story grew, with input not just from my own perceptions but from my parents and my environment. Linda Bayley is a bowler. Linda Bayley is a great bowler. Linda Bayley is the best bowler there is. Linda Bayley is a champion.

Then the idea of Linda Bayley as champion spilled over into other areas of my life, and was used as the yardstick against which every one of my actions and accomplishments was measured. I was good at writing, and good at math. I played the bagpipes. I could speak English, French, and high school Italian.

As it turned out, none of this was good enough. My father would use these things to chide me for poor performance: “You’re an athlete! You’ve got the math, the music, the languages…” My stepfather would say, “Ninety-six! Where’s the other four percent?”

You’re playing the world’s smallest violin as you read this, right? Poor Linda, you’re thinking, such a success at such a young age! It’s tragic, what that girl went through.

But being a champion is fine until the day you’re not, until you refuse to go through the training regimen your father has set out for you and he says, “No wonder nobody likes you, you’re such a bitch. You’re a zero.”

Being a champion is fine until mental illness sets in and all your parents see is a badly-behaved teenager, not a person in desperate need of medical assistance.

Being a champion is fine until the day you look in the mirror and all you can see is a loser.

In the intervening decades, I’ve had long stretches of success interspersed with sick leaves of varying lengths. As I write this, I’m in my eighth or ninth week of another leave, after failing to bounce back from a series of benign criticisms that left me so shattered that I could no longer sit down at my desk without crying. Linda Bayley the champion has left the building; enter Linda Bayley the loser, the zero.

I’m working with a counsellor now who is helping me to see that Champion and Loser are not the only two stories I can tell myself, not the only two roles I can play. It doesn’t matter how strongly my parents reinforced these roles; it doesn’t matter how deeply I bought into the story. The story was false, and there is a middle ground.

My task for this sick leave is to find a way to tell a new story: that of Linda Bayley, the woman who is good enough. I don’t know what that looks like, because I’ve never been good enough unless I was awesome. I hope that when the story is told I will like the person who emerges.

I think I will.

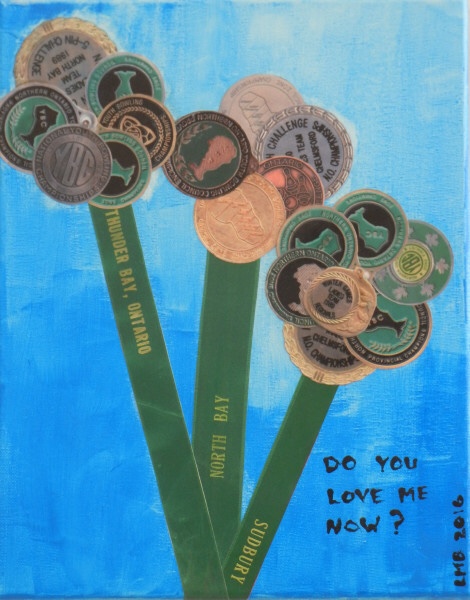

A note about the artwork: “Tokens” was made with pictures of all the bowling medals I won, including the National silver medal I won in 1986. I am forever grateful to Kim Mullin for helping to draw this work out of me.

Previous

Next