When I was a teenager, my Dad would hand-write lectures to me and pass them over to me before I got out of his car, back at my mother’s house. He would insist that I read them then and there; I couldn’t get out of the car until I did. He had to make sure that I received his wisdom.

They were infuriating. They actually had the word LECTURE written across the top of each one, along with the sequence number. He really, truly, expected me to benefit from each one, and to save them, and to one day publish them all in a book.

Naturally, I shredded each one into tiny bits as soon as I got inside, angry, futile tears falling onto my hands as they worked.

I can’t remember now what was in any of them, and for the last little while I’ve been wishing I had saved them, even just one of them, so I could re-read them now and know whether my anger then had been justified, or if the problem was that I was a teenager with mental illness.

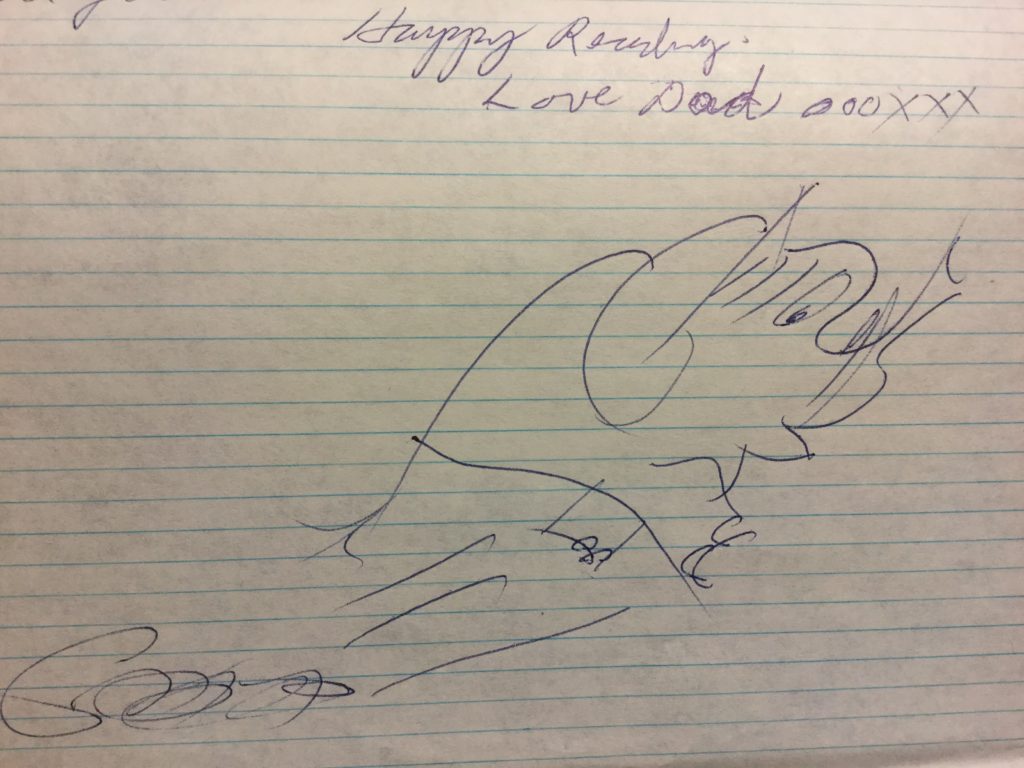

Last night, while looking for a new book to read, I got my wish. Hidden in a copy of Jacques Poulin’s book Spring Tides was a hand-written note from my Dad. Not so much a lecture, though I do remember getting angry over one portion of it when I read it the first time. It was more of a love letter.

It goes like this:

ON BOOKS

May 22 / 2000

Dear Linda

Here are some books. They are my books. You can have them. Now they are your books.

I remember, 24 years ago, you were 3 years old, we were driving down the road to Sudbury Downs to see the horse races. As we drove I was pointing out things to you along the way. You said, “You know everything, Dad.” I said, “No, I don’t know everything.” You said, “Yes you do, and that’s not fair.” I said, “Well, I read a lot of books.” You said, “You don’t share your books with me.” I said, “You can’t read yet, but when you can read you can read my books.”

I was pleased when you came to my house to get information for your school projects. When the presenters of your awards at high school graduation were describing you, your attitude, & your original approach to projects, they were describing me. I knew I had done something right with you.

My mother taught me to read and write and solve puzzles before I went to school. The quest never ends. Books go from the beginning of time (both real & imagined) to the end of time (both real and imagined). Everyone who writes a book will tell me something I don’t know. Each has a way of looking at a place or an object that I have never seen.

When you read my books, you read about me. You will find out where I have been, & where I have never been (& probably not know which is which). You will know what I dream about, what I think about. I have passed on knowledge to you mostly in the oral tradition, & I know you remember. I have not written a book; but I have written enough to fill a book.

By now you are accumulating a body of knowledge of your own. (Books that I have never seen or read.) Your love mingles with mine & the rest of humanity. Your quest never ends.

He signed the letter with the Running Elephant cartoon that graced most of his notes and cards to me over the years. Although the part of the letter where he claims my personality and accomplishments as his own still angers me, I can’t help but smile at the sight of Running Elephant, my old friend.

I don’t remember all of the books that came with this letter. Spring Tides, obviously. Stars in my Pocket Like Grains of Sand, by Samuel R. Delaney. A couple of others. I haven’t read them all yet, because I don’t feel quite ready for them.

My dad wanted to share his knowledge of the world with me. He didn’t necessarily go about it the right way, but I have to believe that his intentions were pure. And he wasn’t wrong about the books: all of humanity is in novels, and every time I read the story of another person, real or imagined, I learn more about the story of me.

When my Dad left town in 2003, and when he died in 2006, I found myself in the position of having to go through his possessions, but especially his books. Both times I found books that had scraps of paper marked “Linda” tucked inside them, books he had meant to share with me when the time was right. All of those books are in a box now, waiting for me, for when I am ready to learn more about the worlds my father has seen and dreamed.

This was the legacy he wanted to leave me. This was the most precious thing he felt he had to offer me: knowledge. My father was a deeply flawed man, and a lot of his methods caused me a great deal of harm that I am still working through today. But thinking of all those books set aside for me, I know this for sure: he loved me. He loved me. And he still has things to teach me, for better or for worse.

Previous

Next